|

|

Welcome to Popular Information, a newsletter dedicated to accountability journalism.

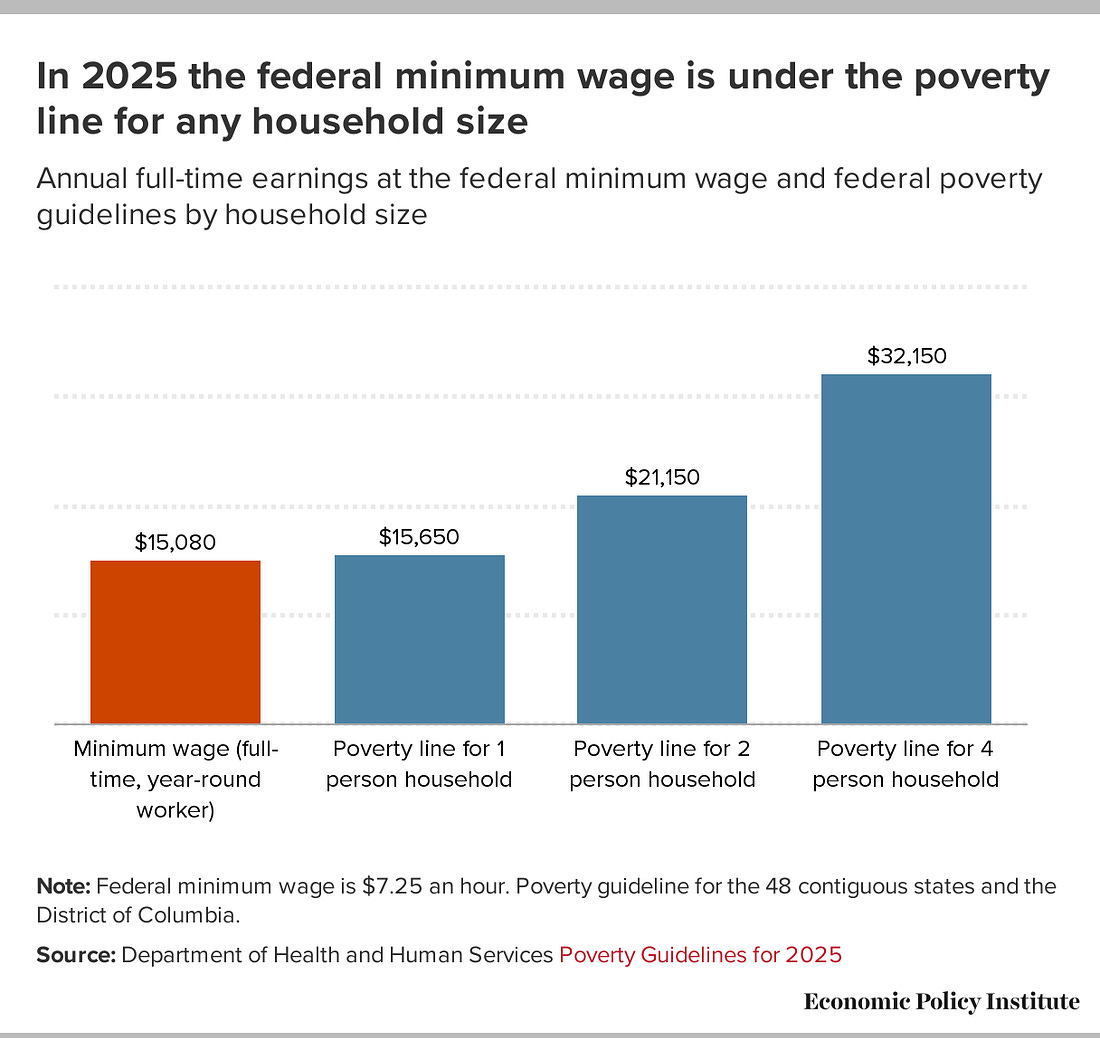

Americans who work 40 hours a week, 52 weeks a year, at the federal minimum wage no longer make enough money to keep themselves out of poverty.

For workers in the 20 states that have not passed their own higher minimum wage, working full-time at $7.25 brings in $15,080 per year, short of the poverty line of $15,650 for a single-person household, according to a new report by the Economic Policy Institute (EPI).

The federal minimum wage has lost 30% of its value since the last time it was raised in 2009. In 2025 dollars, the 2009 minimum wage was worth $10.37, and at its peak — reached in 1968 — the federal minimum wage was worth $12.22.

Since 1968, the ability of Americans working full-time, minimum wage jobs to support themselves has eroded. And the problem is likely even worse than what is shown by comparing the minimum wage to the poverty line.

The Census Bureau’s official measure of poverty (OPM), which is the basis for determining the poverty line, is simply a multiple of the cost of a minimum food diet for each person in a household. It does not directly account for other necessities such as housing, clothing, and utilities.

Based on the OPM, 4.5% of American workers ages 18-64 are living in poverty. But when using another measure that directly accounts for other necessities, that number jumps to 7% — or 10 million working Americans.

President Trump himself has acknowledged that the federal minimum wage is a “very low number” and told NBC in December 2024 that he would “consider” raising it, but just over 100 days into his term, he has not announced any plans to do so.

Minimum wage myths

In the same NBC interview from December, Trump cautioned that a minimum wage hike would devastate small businesses and lead to job losses. He said, “In California, they raised it up to a very high number, and your restaurants are going out of business all over the place. The population is shrinking, it's had a very negative impact.”

This is a popular refrain for opponents of raising the federal minimum wage. But it is not true.

There is a hypothetical level at which a minimum wage hike would have a significant impact on job numbers, but economists have found that none of the current proposals ($17 per hour by 2030 being congressional Democrats’ most recent proposition) would push the minimum wage to that point.

Instead, most studies have shown that increasing the minimum wage within a reasonable range — and indexing it to keep up with inflation — would create little or no job loss. But it would substantially increase the earnings of low-wage workers.

A review of studies on minimum wage over the last 35 years by Arindrajit Dube, an economics professor and researcher for the National Bureau of Economic Research, and Ben Zipperer from EPI found that the data shows that job numbers would decline slightly if the minimum wage was raised, but the total earnings of all low-wage workers would still increase.

Dube and Zipperer found that the wages subtracted because of job losses only offset a small percentage of the gains from a minimum wage increase. Aggregating all of the studies, they found that job losses reduced the increase in combined earnings of low-wage workers by 13%.

However, Dube and Zipperer pointed out that many of the studies are focused on specific groups of low-wage workers, like teens working part-time after school. When only taking into account the studies that looked at all low-wage workers, they found that the combined earnings of all low-income workers would increase by 2% more than the amount of the minimum wage increase, meaning that new jobs would be created.

Dube explained in a column for the Washington Post that when minimum wage increases, it can appear that jobs are disappearing because suddenly there are no more jobs that pay less than the new minimum. But these jobs are not vanishing; they are nearly all replaced by jobs that pay the new minimum wage.

Valuing work

In addition to opposing raising the minimum wage, Republicans also want to make it harder for low-income families to access federal assistance programs. Republicans have proposed adding work requirements to programs like Medicaid and SNAP, arguing that work requirements would “encourage people to work” and that federal assistance programs allow people to depend on the government.

But this is false. The reality is that most people who receive these benefits already do work. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “[n]early 2 in 3 non-elderly adult Medicaid enrollees currently do paid work, and most of the rest have a disability, are caring for family members, or are attending school.” Additionally, “86 percent of SNAP households with working-age adults who are not receiving disability benefits report earnings during the year.”

Since many people enrolled in Medicaid and SNAP already have jobs, work requirements are not an effective way to increase employment rates. According to a 2022 Congressional Budget Office report, “[w]ork requirements are less likely to lead to employment and more likely to reduce income” for people who “have conditions that make it difficult to find and keep a job,” such as disabilities or caregiving responsibilities.

States that have attempted to use work requirements to boost employment have found them counterproductive. In 2018, Arkansas implemented a work requirement policy for Medicaid with consequences for noncompliance, which resulted in “18,000 losing coverage for failure to meet work or reporting requirements.” In 2019, a federal judge struck down the state’s work requirement. According to KFF, Arkansas’ work requirements caused “no significant change in employment” and vulnerable enrollees, including those experiencing homelessness or with disabilities, “were the most likely to face barriers in complying with the requirements.”