|

|

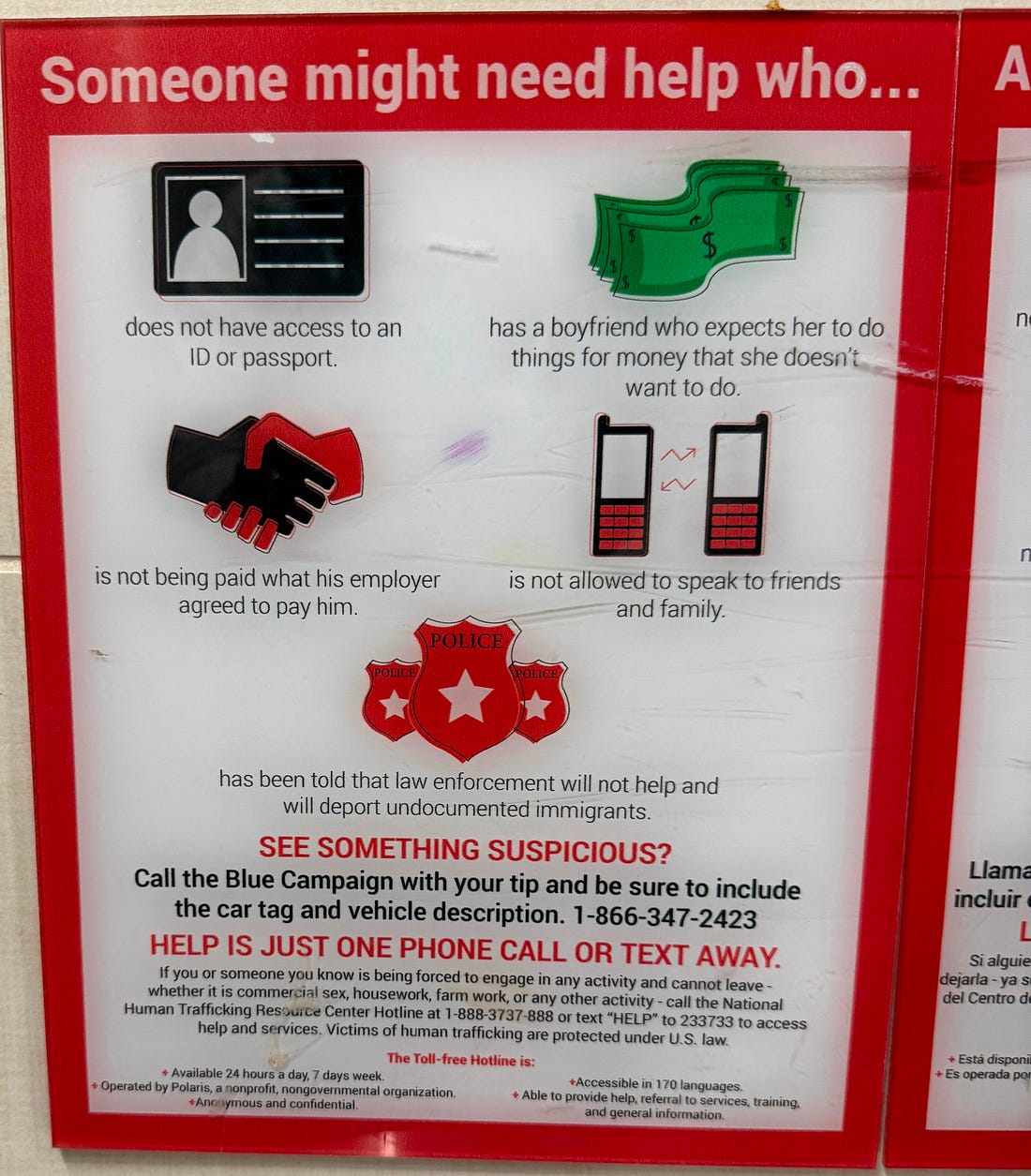

When I was U.S. Attorney in North Alabama, we fought hard to get signs like the one below up in airports, train stations, and bus terminals. This was before human trafficking had become a cause célèbre, but there was already a dedicated group of community organizations and individuals who understood the importance of working together to help people who were being held in modern-day slavery, which includes sex work, forced labor, and domestic work.

The signs made a difference. They helped individuals. They also raised public awareness. States like Alabama adopted their own anti-human trafficking laws, which permitted them to prosecute cases in addition to the ones being done federally.

Because many of the victims came from Mexico, the Caribbean, Central America, and Latin America and were brought into the country illegally by the people who now profited from trafficking them, they were easy to control. They lacked legal status to be in the U.S. Their passports or other papers from their countries of origin were held by the traffickers. And they were told that if they tried to escape, they would be deported, often back to countries where their lives or well-being would be in danger, or that their families would pay a price.

Progress combatting human trafficking was slow, especially early on. Law enforcement learned that drug traffickers, especially cartel-linked ones, were also trafficking in people. Educating police officers so that they knew what to look for during traffic stops was a big breakthrough. When trainers were able to go to roll call and talk with officers heading out on their shifts about looking for people who seemed vulnerable for a number of reasons, arrests started to happen. Arresting little fish produced bigger fish. And victims were freed from the horrible circumstances they were living in. Human trafficking cases were among those I was most proud to see my office prosecuting.

There was also education for hotel desk workers, medical professionals, and others likely to come into contact with people being trafficked. They were taught to look for the signs. They helped too. But educating the community was one of the most impactful steps. Community members began to report suspicious situations. For instance, from Arizona: “Trafficking suspect in Scottsdale arrested after neighbor noticed something was 'off,' police say.” In Alabama: “Investigators with the Shelby County Drug Task Force thank neighbors for their help in a human trafficking operation they say saved several victims.”

Human trafficking is a complicated problem that can only be solved if victims and witnesses feel comfortable seeking out law enforcement and if police, community workers, and neighbors view people being trafficked as victims who need their assistance. Polaris is one of the organizations that does outstanding work on these issues. They collect and report on data. They acknowledged in a report that it’s very difficult to get data on the immigration status of victims. Between 2015 and 2018, that data was collected for about 36% (17,000 likely victims) of those who were reported to the Trafficking Hotline. About 53% of those victims were not U.S. citizens or legal permanent residents. It’s likely that the group whose citizenship status was not reported leaned heavily toward people who lacked legal status, so the true percentage is likely much higher.

At her confirmation hearing, Attorney General Bondi said her commitment to “make America safe again” meant she would focus on violent crime, human trafficking, and the opioid crisis. But, that conflicts with this administration’s top priority, deporting anyone they can lay hands on who is here without legal immigration status. That means victims can no longer feel safe coming forward—it’s unclear whether immigration relief that permits undocumented people to remain in the U.S. while cooperating with criminal investigations and testifying in cases is still available. In addition, Trump’s immigration sweeps may mean that victims are unknowingly being deported. And it’s not just victims. Witnesses, who are often drawn from these same communities, are far less likely to come forward. After the well-known spectacle of federal agents in a state courthouse in Wisconsin, leading to both the arrest on an immigration warrant of a man with a case in front of her and the judge herself, even the courts are not a safe haven.

The bottom line is that brown-skinned victims of human trafficking are far less likely to receive and seek help, even if, on paper, the new attorney general says those cases are a priority. The Civil Rights Division, now in the process of being dismantled, ran a human trafficking prosecution unit that worked with U.S. Attorneys’ offices nationwide and other federal and state agencies. The website for the unit, which is still up as of tonight, notes that while not all victims of trafficking are migrants who lack legal immigration status, “undocumented migrants can be particularly vulnerable to coercion because of their fear of authorities.” But this administration doesn’t see these people as victims; instead, it views them as dangerous and immediately deportable. That means that the signs we have in our airports and that are in transportation hubs, restaurants, hotels, and police stations across the country will no longer help to protect some of the marginalized people who need help the most.

When I saw that sign in the airport last week, I was reminded of the valuable community partnerships I was lucky enough to be a part of and the good work we did together. But then I realized how much of that is being lost. This administration is not making America great again. Not by any stretch of the imagination. Watch what they do, not what they say.

We’re in this together,

Joyce

You're currently a free subscriber to Civil Discourse with Joyce Vance . For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.