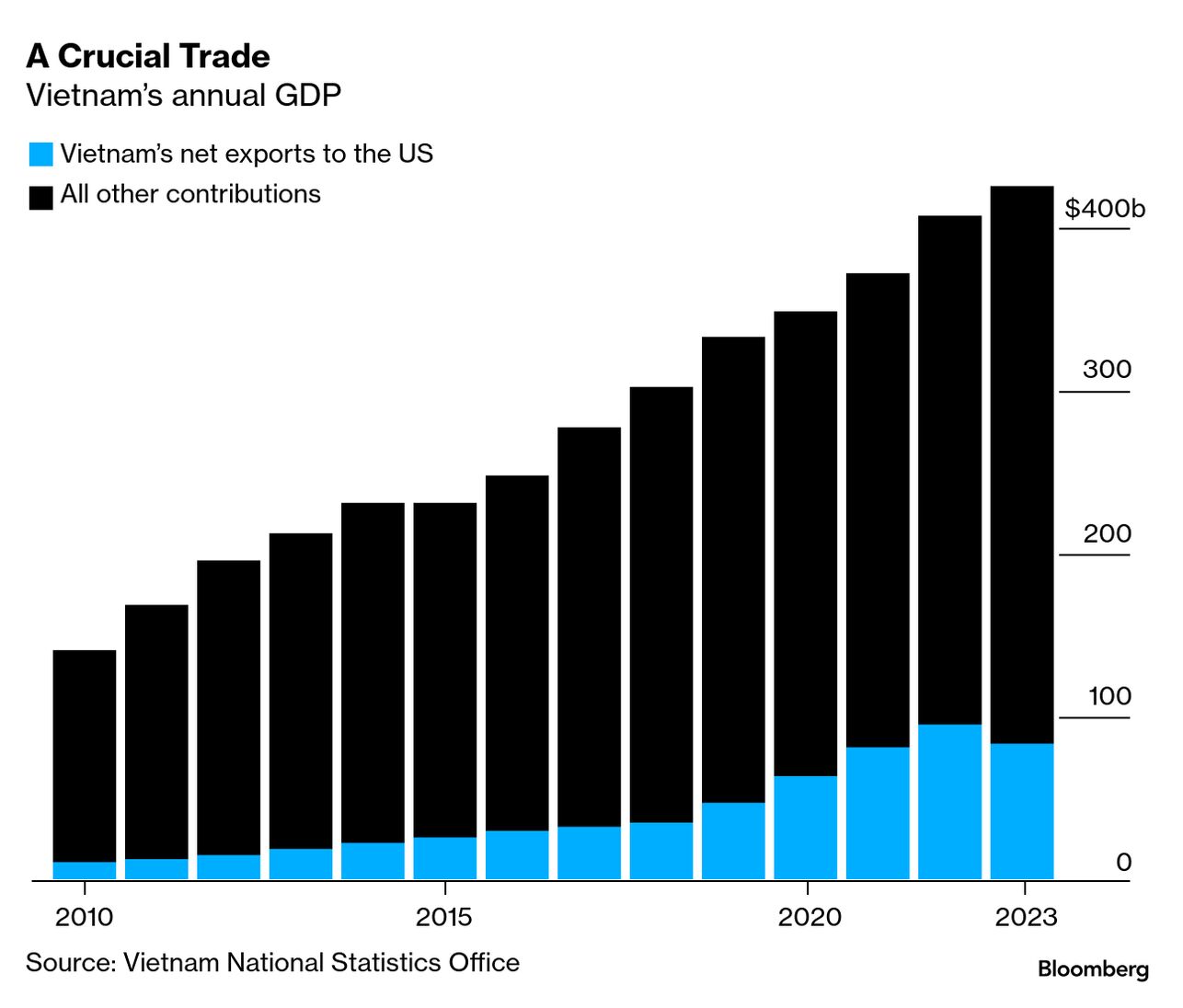

| Welcome to Bw Reads, our weekend newsletter featuring one great magazine story from Bloomberg Businessweek. Today Anders Melin, Nguyen Dieu Tu Uyen, and Francesca Stevens take a look at Vietnam’s economic boom and how it might be crushed by US tariffs. President Donald Trump’s eccentric understanding of global trade flows put Vietnam in an especially difficult position, because the country is an export powerhouse, but its citizens can’t afford expensive imports. You can find the whole story online here. If you like what you see, tell your friends! Sign up here. It’s been several weeks since US President Donald Trump declared his global trade war, but Dinh Ngoc Hien is still busy tending to her stream of customers. One by one, they pluck cigarettes, noodles, eggs and soda from the shelves of her convenience store in Dong Nai, a heavily industrialized province just east of Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam’s business capital. Hien has been here since dawn, and she’ll remain after dusk. Then she’ll lock up, get on her motorbike and zip through the bustling streets of a place that could have more to lose from Trump’s policies than almost any other. The president’s “Liberation Day” tariffs, unveiled on April 2, targeted Vietnam with a 46% rate—one of the highest for any country, threatening to devastate large swaths of its economy. The nominally socialist nation of 100 million has woven itself tightly into global commerce since the late 1980s, when it began allowing free enterprise and started mending its war-ravaged relationship with the US. Adidas, Apple, Intel, Levi Strauss and Samsung Electronics have all set up manufacturing bases here, along with hundreds of other international companies. Today, net exports to the US account for around one fifth of Vietnam’s gross domestic product.  While the tariffs have been put on hold until July and are the subject of multiple court challenges, the fear they’ve caused across Vietnam continues—especially in Dong Nai. When the 34-year-old Hien was a child, the Delaware-size province was a place of open fields and rice paddies, where farmers toiled much as they had for centuries. Now its western flank is an urban extension of Ho Chi Minh City, a sprawl of highways and industrial sites girded by commercial strips where workers can spend their extra cash. Most of Hien’s customers have jobs in nearby factories; so do her husband and her sisters and their spouses. “All these changes are good,” she says. “Our lives are much better now. We live in bigger houses, and everyone in the family has a motorbike.” With business brisk, she has plans to expand: “I want to see myself grow into a real entrepreneur.” Hien’s ambitions, and those of millions of her compatriots, will hinge in part on what happens in the coming weeks. The Vietnamese government has dispatched several delegations to Washington and pledged to remove what the country’s trade minister described as “barriers that hinder investment and business activities.” It’s promised to eliminate illegal transshipments, whereby Chinese companies evade import controls by sending their wares to Hanoi or Ho Chi Minh City and designating them as “Made in Vietnam”; Trump’s trade negotiators describe this as a major problem. US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has also suggested that deals with Vietnam and other Asian countries could require them to impose economic measures of their own against China, a crucial Vietnamese trading partner.  Employees leaving an industrial park in Dong Nai. Photographer: Maika Elan for Bloomberg Businessweek And in addition to those potential concessions, Vietnam has offered something that might be more impressive to a president who’s openly using the office for personal profit: facilitating the development of a Trump-branded golf resort that went from proposal to construction in a matter of months. The White House has said that Trump complies with conflict-of-interest rules; the Trump Organization, his family real-estate company, said in a statement that its Vietnam deals were signed before last year's election, and that the firm has "zero connection to the administration." Its local partner, Kinh Bac City Development Holding Corp., did not respond to a request for comment. Still, it’s not clear whether any of this will be enough to change Trump’s plans. The UK recently reached an accord with the White House that exempted its steel industry from US tariffs and reduced the levies on a limited number of British-made cars—but that left unchanged the 10% rate on most other products announced in April. Moreover, even traditional US allies have learned that an agreement with Trump can be abrogated in the time it takes him to post to Truth Social, and for almost any reason. The tariff assault has been particularly stunning for Vietnam, given its unique history with the US. American bombing devastated large parts of the country in the 1960s and ’70s, contributing to the deaths of as many as 3 million Vietnamese—at least half of them civilians. More than 58,000 Americans were also killed in the conflict. The normalization of relations, 20 years after the end of hostilities, marked an extraordinary historical pivot. The two countries soon grew closer, partly thanks to US policymakers encouraging companies to “friendshore” their production away from China. Both Republican and Democratic presidents nurtured the relationship, which has extended in recent years to include some security cooperation. So did successive Vietnamese leaders, despite the lingering effects of the war: Undetonated bombs continue to kill people each year, and the descendants of those exposed to Agent Orange, a toxic defoliant, suffer abnormal rates of cancer and birth defects. Trump’s tariff announcement, then, wasn’t just another policy decision. It was a direct strike on decades of political and economic rapprochement, delivered with the stroke of a pen. If Trump drives the countries apart, “it will be bad for the US, and worse for Vietnam,” warns Stefan Selig, who served as undersecretary of commerce for international trade during the Obama administration. “The US consumer is going to lose. US strategic interests are undermined. And, most unfortunately, the Vietnamese—trying to pull themselves up from poor to middle class—are going to lose. It’s heartbreaking, frankly.” Keep reading: US Tariffs Threaten to Derail Vietnam’s Historic Industrial Boom Keep up with the latest numbers in the Trump tariff tracker |