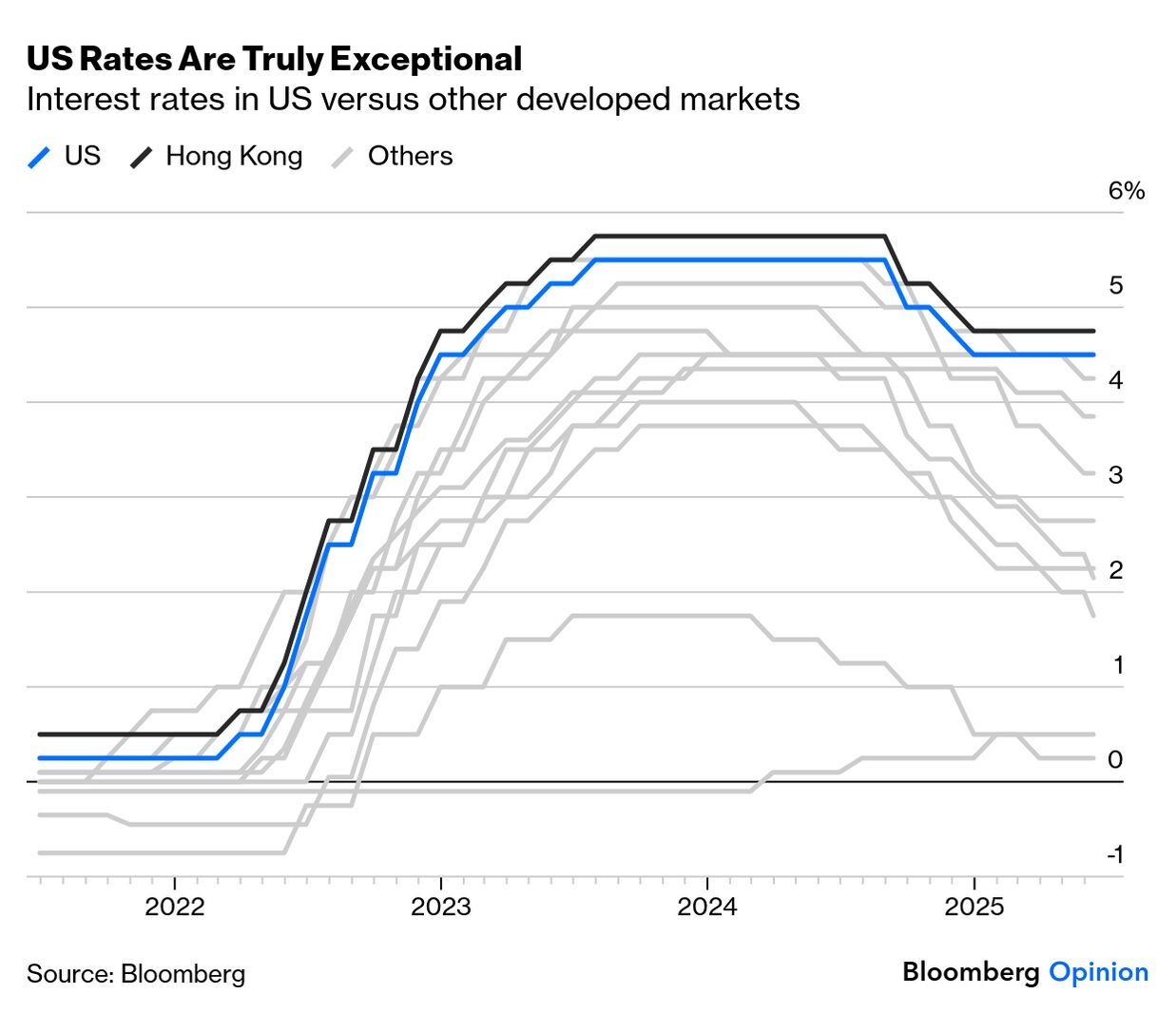

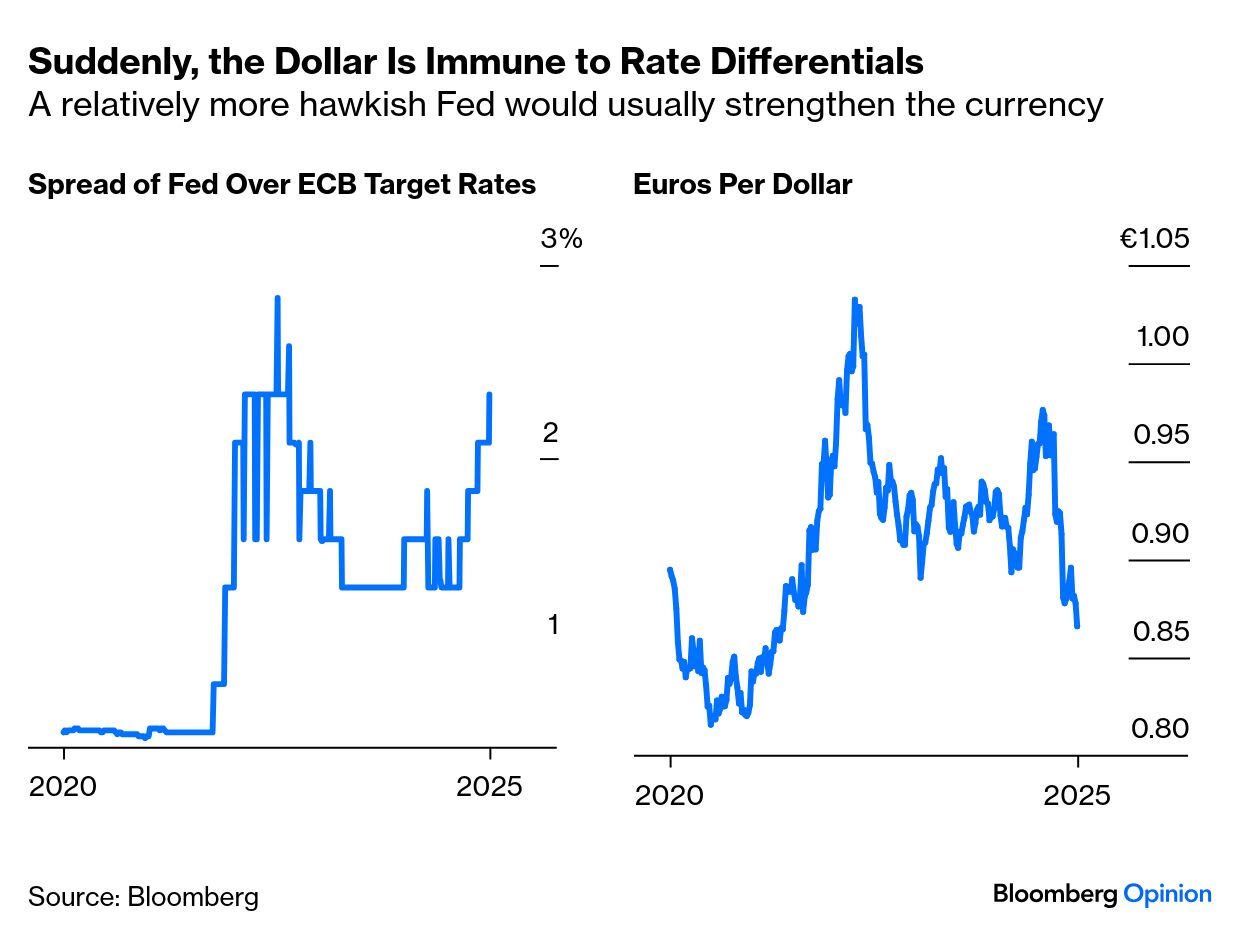

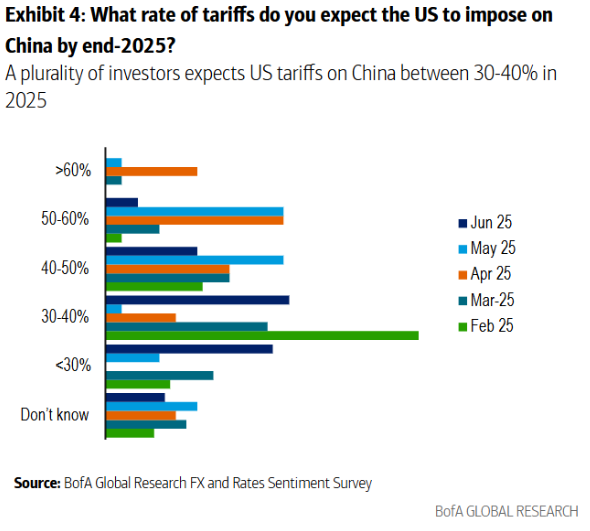

| Federal Reserve Chair Jay Powell has barely a year left to fortify his legacy. For all the plaudits he gets for steering an aggressive hiking cycle without crashing the economy, it will be forever tarnished by misdiagnosing post-pandemic inflation as transitory. That misjudgment proved costly to monetary policy credibility. For now, that’s water under the bridge. The Fed’s management of the fallout has been as successful as anyone could have hoped. Powell’s current headache is gauging the impact of President Donald Trump’s tariffs on prices. There’s little sign of the new duties in inflation data so far, and the “transitory” theory sounds more plausible this time. But after his previous mistake, it makes sense to err on the side of caution. US tariffs are slated to affect all imports, while the impact on other countries should be more limited as they affect only their trade with America. As a result, US rates look like ever more of an outlier among developed nations:  Only Hong Kong, which attempts to keep its own dollar pegged to the greenback, has higher rates. Differentials with the rest of the world are rising. That would usually push the dollar upward — but in the weird conditions created by trade policy uncertainty, the currency has been falling (before a mild rally on the news of the Israeli attack on Iran). The 180-degree turn in the dollar’s behavior is clearest if we compare the spread between fed funds and the European Central Bank’s target rate, which is widening, with the dollar-euro exchange rate. (If you are reading this on the terminal, try opening this chart in GP):  The Fed’s wait for clarity, coupled with the dollar’s slump, has created an opportunity for emerging markets to resume easing. As Points of Return has pointed out several times over the last year, coordination among central bankers on an easing cycle is as necessary as it is for mountaineers on a descent. That’s worrying because monetary authorities, roped together for safety, appear to be navigating separate terrains in their climbs down. As the inflation spike took hold from 2021, emerging central banks were visibly more proactive, and they have generally coordinated better both the ascent and the descent. Developed markets, as shown in the chart above, are growing distant from each other — a problem on mountains and in money. Trump’s tariffs and their effect on inflation expectations have derailed easing cycles for a while. It’s not only the Fed that finds a “wait and see” approach more logical. But now, with optimism rising that the US trade policy bite won’t be so bad, cuts are the norm once more. This is the latest edition of our diffusion index, in which rate cuts or hikes by each of 52 central banks counts equally: Several developed countries have also joined in the descent, including the ECB. It’s premature to declare victory, but central bankers who cut rates are likely to feel justified in believing they’ve made enough progress in taming inflation and can now tweak to stimulate growth. The weak dollar and the Fed’s inertia offer them additional support: The significant exceptions are the South American nations of Argentina and Brazil, which have their own issues, and Turkey, still trying to recover from the disastrous easy-money policy forced on its central bank by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. There are myriad reasons why a weak dollar matters more to central banks in emerging markets. Gene Goldman, Cetera’s chief investment officer, explains that this has to do with their debt dynamics. When the greenback strengthens, it increases the cost of servicing dollar-denominated debts. Now, with the dollar weakening, EMs can stimulate their economies without worrying that this will push up their debt costs. Bank of America’s Ralf Preusser observes that Trump’s three-month tariff pause with China led investors to mark down their fears of higher levies:

Source: Bank of America

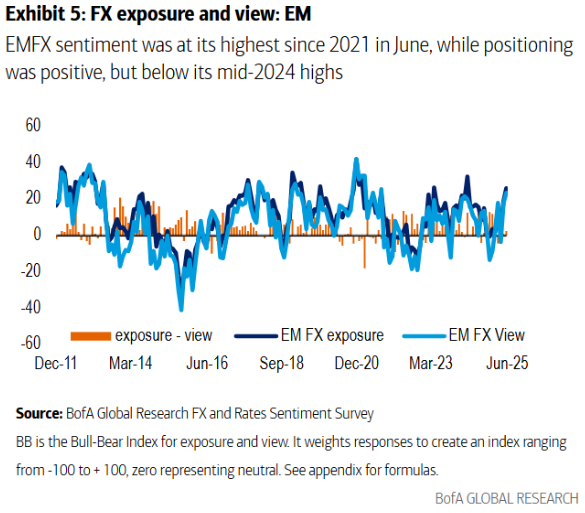

BofA’s measure of emerging market FX sentiment has reached its highest level since 2021, before the Fed started tightening. Preusser notes that positioning remains below pre-US election levels, suggesting that there is still room for the EM rally to run:

Source: Bank of America From here, the market is convinced that the Fed’s next move – whenever it comes — will be a cut. That should also be dollar negative. The Bloomberg World Interest Rate Probabilities function suggests that markets are pricing in a steeper descent, eventually leading next year to a significantly lower terminal rate, than they did back in January. That implies pessimism about the US economy, and makes it harder for the dollar to stage a rally: Powell’s consistently cautious tone contrasts with investors’ expectations. That caution may yet be vindicated by the fresh possibility of higher oil prices. Ryan Sweet of Oxford Economics argues that the impact of tariffs on inflation and the labor market are still likely to be the Fed’s primary drivers: We’re comfortable with our forecast, but with an economy vulnerable to things like the escalation in Middle East tensions, the Fed should be nimble. A significant and sustained increase in oil prices could bring the rate cut forward by a meeting because of the damage it will do to the economy, which is harder to fix than waiting out the temporary acceleration in headline inflation.

Bloomberg Economics’ Anna Wong suggests that the bar for looser policy is high, as the Fed appears unimpressed by four consecutive soft inflation reports. It may lean on internal models that predict an eventual tariff-driven surge in prices. Although growth appears solid, Wong sees Powell emphasizing “wait and see” due to policy uncertainty, with almost the entire Federal Open Market Committee seeing upside inflation risks. The greatest interest in this week’s meeting will be on the new “dot plot” of policymakers’ rates predictions, the first since March.  The Fed can afford to hang back. Photographer: Matthew Williams-Ellis/Universal/Getty More rate cuts cannot be ruled out as Switzerland, Sweden, and the UK hold their own meetings. Idiosyncratic factors could drive decisions. Sweden’s Riksbank is projected to ease to 2% after disappointing first-quarter growth. Unless events in the Middle East change things, Bloomberg Economics’ Selva Bahar Baziki forecasts a prolonged pause after this month. “We do not rule out additional reductions in borrowing costs if trade policy uncertainty and sluggish domestic demand persist.” The Swiss National Bank could cut by 25 basis points to 0.0% on Thursday. A return to the “zero bound” will have a psychological impact, but it’s hard to see the bank then forging back into negative territory. The Bank of England is expected to hold at 3.4% after inflation delivered a nasty shock by rising in April. Tariffs have made the Fed’s descent from the mountain slower and more hazardous. The weaker dollar has made the going easier for other central banks. That’s provided a more reliable harness as the mountaineers make their way back to base. As for Powell, with inflation still lurking, the weakening dollar makes it easier for the Fed to stay put on its own ledge. |