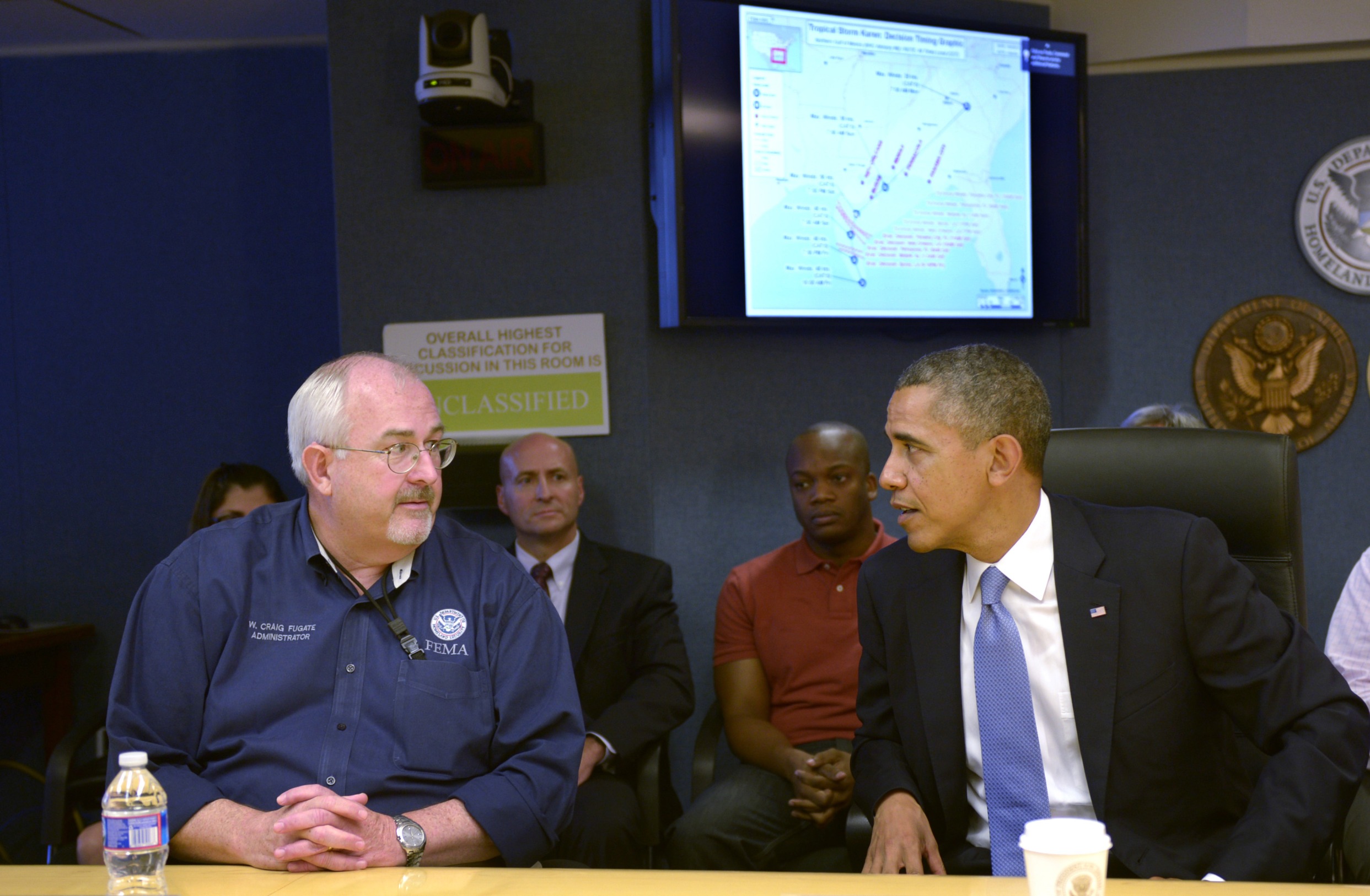

| By Eric Roston The US has spent nearly $1 trillion dollars on disaster recovery and other climate-related needs over the 12 months ending May 1, according to an analysis released Monday by Bloomberg Intelligence. That’s 3% of GDP that people likely would have spent on goods and services they’d prefer to have, and amounts to “a stealth tariff on consumer spending,” analysts write. Hurricane Helene struck Florida in late September 2024 as the most powerful storm ever to hit the state’s panhandle. Its rampage was followed a week and a half later by Hurricane Milton. Those two storms caused $113 billion in damage, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The Los Angeles fires in January added another $65 billion to the national total. The new report, “The Climate Economy: 2025 Outlook,” draws on data from dozens of public sources to demonstrate the volume of disaster-related spending, which represents $18.5 trillion globally since 2000. The biggest drivers of this trend in the US are insurance premiums — which have doubled since 2017 — post-disaster repair spending and federal aid. Read more: US Home Insurance Priced Too Low for Climate Risks Overall, increased climate costs from insurance premiums, power outages, disaster recovery and uninsured damage are responsible for $7.7 trillion, or 36%, of US GDP growth since 2000. Risks are rising both from climate change, as it increases the severity and frequency of extreme weather, and from development that is insufficiently focused on resilience. Andrew John Stevenson, a Bloomberg Intelligence senior analyst, assembled a basket of 100 companies that have stood to gain from this spending. The firms, which span sectors from insurance to engineering, materials and retail, together outperformed the S&P index by 7% in each of the last three years. Insurance is a “hidden burden of the climate economy,” write Stevenson and Eric Kane, director of ESG research for Bloomberg Intelligence. Wind, water and fires led insurers to raise premiums by as much as 22% in 2023 alone. They may rise again more than 6% this year. These costs are not included in the Consumer Price Index, which means that national spending on housing, thought to be about 35.5% of the total, may actually be higher than 40%. Federal spending covered as much as a third of climate-related costs, for both disaster prevention and recovery, until 2016. The share has fallen in the last couple of years to only around 2%, and federal budget freezes and proposed cuts may diminish the outlook further. That puts stricken communities at greater need to issue general debt — which their post-disaster economies may not always be resilient enough to pay off. Read the full story on Bloomberg.com. One question with...Craig Fugate | By Leslie Kaufman President Donald Trump has repeatedly said he intends to whittle down or phase out the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and last week he gave a rough timeline for that: “after hurricane season.” “We want to wean off of FEMA, and we want to bring it down to the state level,” Trump told reporters on June 10 during a briefing in the Oval Office. Calls to reform FEMA — as it responds to more frequent climate-driven disasters — aren’t new. Previous laws and proposals have tried to encourage states to be more independent and to carry out more pre-disaster mitigation. Nor are concerns over the agency’s costs and bureaucracy unique to Trump and his allies. Last month, two members of Congress released a draft of a bipartisan bill that would amend the Stafford Act to address some long-running criticisms of FEMA. The draft bill was released by Missouri Republican Sam Graves and Washington Democrat Rick Larsen, who are the chairman and ranking member, respectively, of the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure. Bloomberg Green recently spoke with Craig Fugate, who ran FEMA for eight years under President Barack Obama. Fugate said the agency “was never intended” to do some of what it does today and weighs in on some ways it might reform.  Then-FEMA Administrator Craig Fugate, left, talks to President Barack Obama at FEMA’s National Response Coordination Center in Washington, DC, on Oct, 7, 2013. Photographer: Shawn Thew/EPA Given that FEMA is likely to stay around in some form, what are some of the changes to it that have the most chance of actually being enacted? Well, there is the Public Assistance Program, which is the reimbursement to state and local governments and eligible nonprofits and faith-based institutions — the last [group] was added in the first Trump administration — to rebuild. And the rap on that is the complexity of administering it. Take a fire station that is destroyed in a flood and has no insurance. FEMA would reimburse the local government 75% of the cost of rebuilding. But there’s lots of caveats. FEMA has to look at what was the condition of the station, how big it was. Then they would agree to replace the station as it was, and build in a little bit of mitigation, maybe elevating it. When this is finally resolved, the city has to go out and get bids. FEMA has to review that and approve a design. And then the city has to go out and get financing. They have to start the construction. In each step, FEMA goes back and reviews the work being done, and they actually will send inspectors out to the job site to make sure that the station is being built back the way the approvals say it was. If the city says, “Hey, that fire station got flooded, so we want to move it,” that’s more paperwork. If they say, “Hey, we need to add another bay, since the fire station was too small in the first place,” FEMA will not approve the new bay. The locality has to pay for that out of pocket, and that will have to be kept separate from the reimbursement for the primary replacement. And this process can drag on for years. So what is being proposed in the House bill is what they call an alternative project. Essentially, it says, “We’re going to treat this like an insurance policy: You’re going to come up with an estimate of what it’s going to take to replace that station, based upon the current costs, and if you can get the designer of that replacement to put their seal on it, we’ll [give] you 75% of that, and we’re done.” If you took the House [draft] bill and you fully implemented it, you could probably do everything that FEMA does today with a substantially reduced workforce. The [contract] recovery workforce can be anywhere from 10,000 to 20,000 people, depending on how many disasters are being closed out. And some of these disasters are decades old, and you’re still paying contractors to handle the reimbursement and management of those grants. There is also much tougher language [in the draft bill] about insurance requirements. If FEMA pays you out to rebuild after a disaster, you have to get coverage. You can’t come back again. That also incentivizes mitigation, since you’ll be paying insurance and repairs yourself. One question not enough? Read the full interview. |