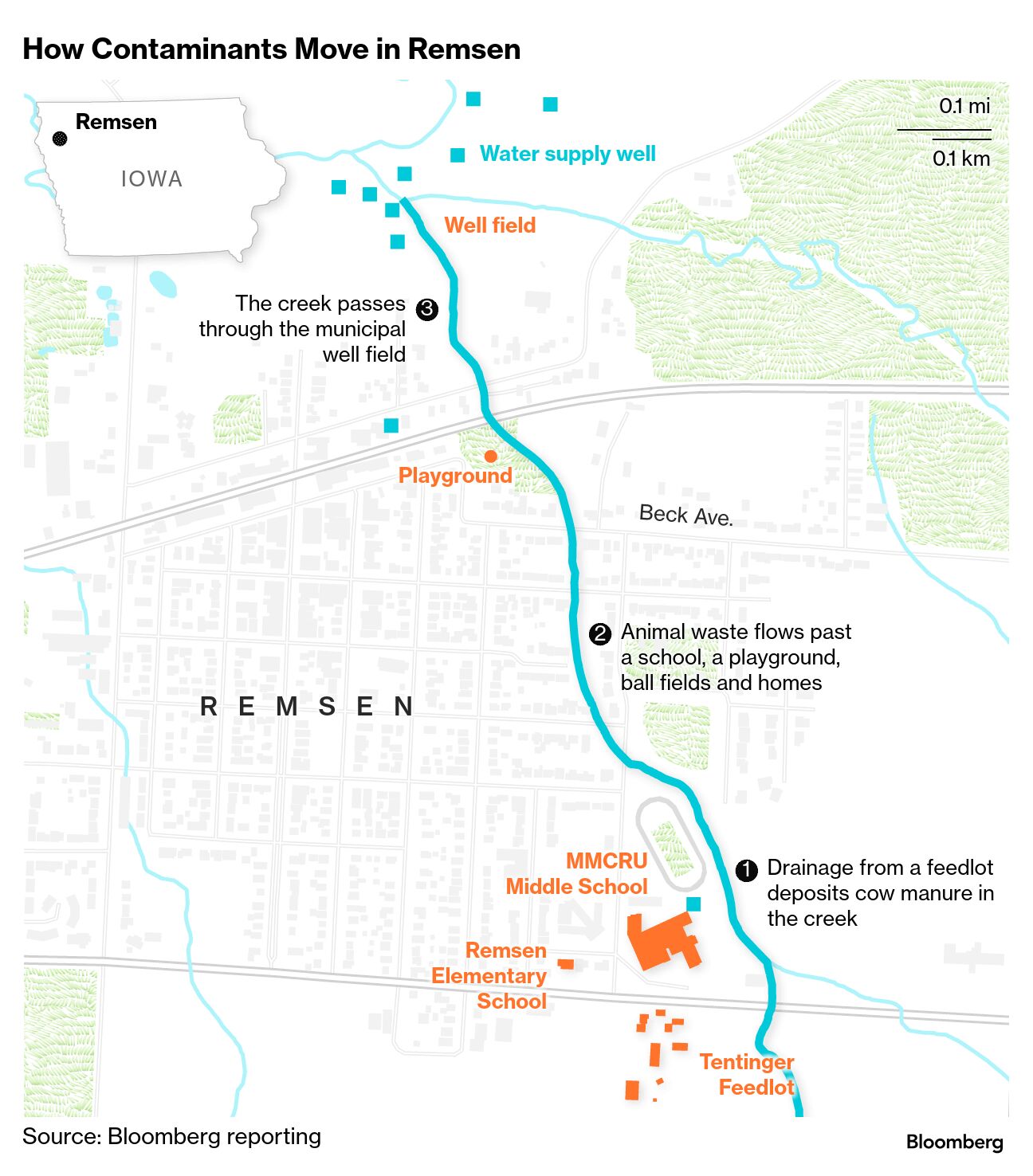

| Welcome to Bw Reads, our weekend newsletter featuring one great magazine story from Bloomberg Businessweek. Today, Peter Waldman writes about the problem of runoff from Iowa’s fields and feedlots, which fills its waterways with dangerous nitrates. It would be fixable if not for the political and economic power of Big Ag. You can find the whole story online here. If you like what you see, tell your friends! Sign up here. In the town of Remsen, in Northwest Iowa, Steven Pick spent 34 years working at City Hall. As the city clerk, he rebuilt Remsen’s ball fields and swimming pool and served as president and vice president of the chamber of commerce. He managed a local baseball team, played third base and pitched. Pick’s proudest endeavor, though, was his determined effort to protect the water supply for Remsen’s 1,600 residents. He’s the first to admit it didn’t succeed. In Iowa, which by some measures has the most polluted water in the US, people who advocate for the environment are widely scorned as enemies of farming. Outside the cities and universities, few dare criticize the state’s $50 billion agricultural industry—the farmers, food processors, tractor makers, chemical companies and ethanol producers that reign supreme in this Kingdom of Corn. Located 40 miles northeast of Sioux City, Remsen lies in the heart of corn country. From May to October, the area is carpeted with sprawling rows of gold and emerald stalks that disappear over the horizon, checkered by occasional feedlots packed with cows and pigs fattened on local grain. Laced across the fields are streams that feed Remsen’s drinking wells and ultimately the Floyd River, a tributary of the Missouri.  Like much of agricultural rural America, Remsen is saturated with pollution from pesticides, hanging in the air as aerosolized particulates or lurking in the dust kicked up by thundering combines. Many, such as glyphosate, the world’s most heavily used weed killer and the active ingredient in Roundup, are suspected of causing cancer and other diseases. But while pesticides are subject to federal health and safety regulations, chemical fertilizers, by far the biggest source of farm pollution, contaminate the water and air virtually unchecked. In Iowa, farmers spread 2.3 billion pounds of nitrogen fertilizer annually on crops, plus almost all the state’s nitrogen-rich manure output of about 50 million tons a year. Although much of the nitrogen, in the form of nitrate, is taken up by crops as nutrients, a third to half runs off with rainfall or is converted to nitrous oxide, a particularly potent heat-trapping gas that makes up 17% of greenhouse gas emissions in Iowa and 6% nationally. Researchers have linked trace exposures to nitrate in drinking water to cancers, birth defects, thyroid disease and blue baby syndrome, a condition that turns infants’ skin blue from asphyxiation. Iowa has the second-highest cancer rate in the US, after Kentucky, and is one of only two states in the country where the rate is rising. (New York is the other.) The contaminated water eventually flows into the state’s rivers and heads more than 1,000 miles downstream to St. Louis, Memphis and New Orleans, before flushing into the Gulf of Mexico, where it creates a hypoxic zone—an area with little or no oxygen, and hence no aquatic life—the size of New Jersey. Pick once hoped the problem could be solved, at least locally. About 20 years ago, as crop yields and feedlots were expanding all over the area, the Floyd River watershed evolved into one of the most polluted in Iowa. Remsen’s wells were hit hard. Friend after friend of Pick’s was diagnosed with cancer, including a few who lived in a single two-block stretch of Remsen beside a manure-clotted creek.  Watch: The Dark Side of America’s Big Agriculture Working with officials from Iowa’s Department of Natural Resources in Des Moines, Pick helped initiate a creative conservation effort to tackle the nitrate problem. They built a task force of farmers, government officials and a hunting group called Pheasants Forever that, over about four years, managed to lower the nitrate concentration in Remsen’s well water by 40%. Pick won an award in 2010 for “exemplary source water protection” from the American Water Works Association at its Chicago gala. “That was one of the big items of my career,” says Pick, a man of 67 years and very few words, particularly about himself. His quest, however, ended in defeat. For years, the state government has crushed almost every effort to hold farmers and agribusinesses accountable for their increasingly dirty footprint. It’s the story of Iowa, and now of the US at large. Federal laws, along with the Environmental Protection Agency, had stood in as nature’s last line of defense in Iowa. Last November the Biden administration EPA, citing excessive nitrate contamination, ordered Iowa to add parts of four rivers to the state’s list of impaired waters needing cleanup, including the drinking supply for about a fifth of Iowa’s population. The state bitterly complained. President Donald Trump’s EPA rescinded the order in July. Now even the feds defer to Big Ag, led in Iowa by the industry’s undisputed champion in the state, the Iowa Farm Bureau Federation. Keep reading: Why Iowa Chooses Not to Clean Up Its Polluted Water |