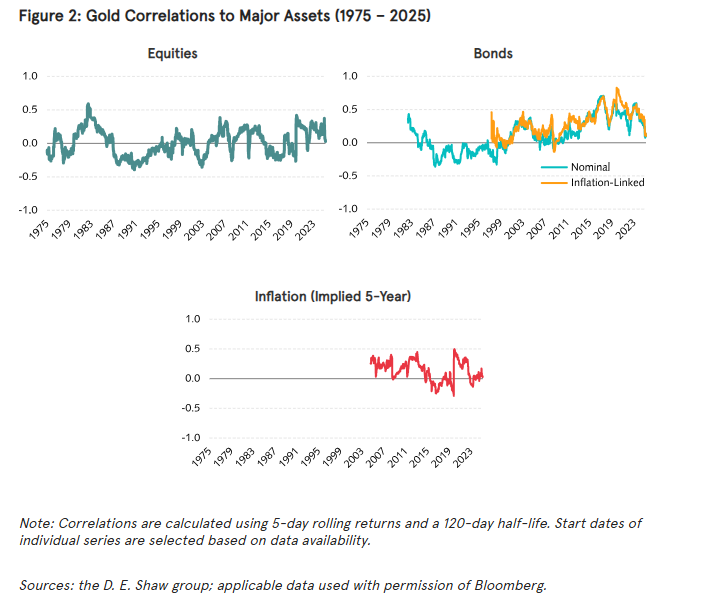

| Gold is up more than 37% for the year, and on course for its strongest annual showing in more than three decades. It’s on a plausible trajectory toward $4,000 an ounce. All of this seems strange as the Nasdaq Composite Index also hit yet another record. But gold is underpinned by a confluence of factors: lingering inflation, monetary policy inertia, and the destabilizing effects of President Donald Trump’s trade nationalism. Questions over the dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency have gilded gold’s status. So far this decade, remarkably, it has beaten the AI-fueled gains of the S&P 500: Gold’s surge measured against the equity performance of the rest of the world is even more impressive, especially in the past year: Central bank accumulation has been crucial. Rohit Paul of Acuity Knowledge Partners shows that, for the third consecutive year, gold purchases topped 1,000 tons. This could continue as geopolitical tension prompts nations to diversify reserves away from the dollar. This is the International Monetary Fund’s measure of China’s reserve gold holdings: Yet gold's Achilles’ heel remains: Unlike equities or bonds, it generates no cash flow. As with any non-productive store of value, its worth hinges on collective belief. So does it make sense to add it to a portfolio? A recent paper from the D.E. Shaw group attempts an answer. Gold’s returns should in theory correlate with key drivers like real interest rates, growth, and inflation, but these factors often offset one another, and empirical evidence is mixed. This chart plots gold’s correlation with US equities, nominal and inflation-linked Treasuries, and implied inflation:  Gold’s volatile relationship with stocks is unmissable — individual drivers dominate at different times, but generally net out over extended horizons. Historically, gold has been positively correlated with inflation-linked bonds, particularly since the Global Financial Crisis. Since 2004, its relationship with inflation has been moderately positive, supporting the hypothesis that its negative connection with real rates offsets its positive expected association with inflation. D.E. Shaw shows that gold’s lack of significant exposure to equity risk could be useful for a portfolio of stocks and bonds: It’s not just gold’s correlation to stocks and bonds that matters: We still need to account for their relationship with each other, one of the most important relationships for investors. After being positive for much of the period from the 1970s through the 1990s, the stock-bond correlation became negative around the turn of the century and remained so for over two decades.

Now, US stock-bond correlations are back at a 27-year high. State Street Investment Management’s Aakash Doshi argues that this enhances the case for gold as a macro portfolio overlay and tail-risk hedge: Gold is not a replacement for government bonds or investment-grade credit. But in a volatile and uncertain inflationary environment, amid lingering geoeconomic risks that could be further exacerbated by trade and Fed policies, gold can incrementally be used as a ‘duration’ and ‘diversification’ hedge.

Having broken $3,500 an ounce last week, gold has mounting momentum. Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s Samantha Dart doesn’t rule out a scenario where damaged Fed independence leads to higher inflation, lower stock and bond prices, and an erosion of the dollar’s reserve currency status. If that were to happen, she argues gold could surge well above the bank’s $4,000 mid-2026 baseline: We estimate that if 1% of the privately owned US Treasury market were to flow into gold, the gold price would rise to nearly $5,000/oz, assuming everything else remains constant. As a result, gold remains our highest-conviction long recommendation in the commodities space.

The metal’s ongoing rally likely has more steam as the Federal Reserve readies to resume its easing cycle. It is hard to tell how long this rally lasts, but in the near term, bullion plainly has all factors going in its favor. -- Richard Abbey Tariffs Begin to Make Themselves Felt | Markets have made their peace with tariffs. After the seizure that followed “Liberation Day,” stocks are back at all-time highs — even though the extra duties have been levied more or less in accord with the April 2 announcement. Judging by the number of stories from all sources about tariffs appearing on the Bloomberg terminal, media interest has also fallen significantly: Thursday’s US consumer price index data will bring the latest update on whether tariffs are indeed raising inflation, as logic would suggest that they must. July’s CPI suggested an impact, albeit still a marginal one. For now, they are having a big effect on government revenues, and almost none on their express purpose of reviving US manufacturing jobs. Uncle Sam is doing very well out of the levies: But tariffs have as yet had no discernible impact on manufacturing payrolls, which have fallen in each of the last four months: Indeed, it’s possible that they’ve had a negative impact as companies respond to levies on imported components and raw materials by reducing their workforce. As Torsten Slok, US economist at Apollo Global Management shows, employment is declining in those sectors most affected: Now that tariffs are becoming an established fact of economic life, clarity on their long-term effects shouldn’t be too much longer. And while media interest and market alarm have died down, businesses sound downright utterly appalled. Tariff mentions in the latest Federal Reserve Beige Book, its regular report of what business contacts are saying, rose from 75 to 100 last month. “Nearly all” districts reported price rises caused by tariffs, while firms reported “at least some hesitancy in raising prices, citing customer price sensitivity, lack of pricing power, and fear of losing business.” Meanwhile, the Institute of Supply Management’s latest survey was a litany of executives’ anger over tariffs — much of which suggests that the need to pay tariffs on components and materials imported to the US means that the effect of the levies could be to drive even more production abroad. The latest ISM report on manufacturing listed the following complaints: - Orders across most product lines have decreased. Financial expectations for the rest of 2025 have been reduced. Too much uncertainty for us and our customers regarding tariffs and the US/global economy.

- Tariffs continue to be unstable, with suppliers adding surcharges ranging between 2.6% to 50%.

- Tariffs continue to wreak havoc on planning/scheduling activities. New product development costs continue to increase as unexpected tariff increases are announced. Plans to bring production back into US are impacted by higher material costs, making it more difficult to justify the return.

- Cost of goods sold is higher due to tariff-impacted goods.

- Export demand is falling as customers do not accept tariff impacts, which likely will require some production transfers out of the US.

- We’ve implemented our second price increase. ‘Made in the USA’ has become even more difficult due to tariffs on many components. Total price increases so far: 24%; that will only offset tariffs. No influence on margin percentage, which will actually drop. In two rounds of layoffs, we have let go of about 15% of our US workforce.

These are complaints from US manufacturers, who are supposed to be the prime beneficiaries of the new tariffs. No importer is going to like higher tariffs, and they’re protected by anonymity, but it’s not in their interest to damage sentiment by infecting the ISM with such negativity unless they really mean it. Very few of them will be committed Democrats. Meanwhile, the ISM services report also had increasing citations of tariff impacts. Choice comments included: - We are starting to see the impact of tariffs on the cost of imported goods... We expect to see the full effect of tariffs in our cost of goods sold by October.

- Tariffs are starting to become a factor in our pricing to specific markets... The intention is not to pass on these costs, but it’s getting harder as this goes on.

- Tariffs continue to loom, and providers are starting to include references to tariffs when requesting price increases.

- It’s all about country specific tariff management. All decision making is currently dominated by tariff considerations.

Governments seem too have settled on a pattern for tariffs; businesses are only starting to decide how to respond. Trade will be back at the top of the agenda before long. |